Exchange rates respond directly to all sorts of events, both tangible and psychological—

- Business cycles;

- Balance of payment statistics;

- Political developments;

- New tax laws;

- Stock market news;

- Inflationary expectations;

- International investment patterns;

- And government and central bank policies among others.

At the heart of this complex market are the same forces of demand and supply that determine the prices of goods and services in any free market. If at any given rate, the demand for a currency is greater than its supply, its price will rise. If supply exceeds demand, the price will fall.

The supply of a nation’s currency is influenced by that nation’s monetary authority, (usually its central bank), consistent with the amount of spending taking place in the economy. Government and central banks closely monitor economic activity to keep money supply at a level appropriate to achieve their economic goals.

| Too much money è inflation è value of money declines è prices rise Too little money è sluggish economic growth è rising unemployment |

Monetary authorities must decide whether economic conditions call for a larger or smaller increase in the money supply.

Sources for currency demand on the FX market:

- The currency of a growing economy with relative price stability and a wide variety of competitive goods and services will be more in demand than that of a country in political turmoil, with high inflation and few marketable exports.

- Money will flow to wherever it can get the highest return with the least risk. If a nation’s financial instruments, such as stocks and bonds, offer relatively high rates of return at relatively low risk, foreigners will demand its currency to invest in them.

- FX traders speculate within the market about how different events will move the exchange rates. For example:

- News of political instability in other countries drives up demand for U.S. dollars as investors are looking for a "safe haven" for their money.

- A country’s interest rates rise and its currency appreciates as foreign investors seek higher returns than they can get in their own countries.

- Developing nations undertaking successful economic reforms may experience currency appreciation as foreign investors seek new opportunities.

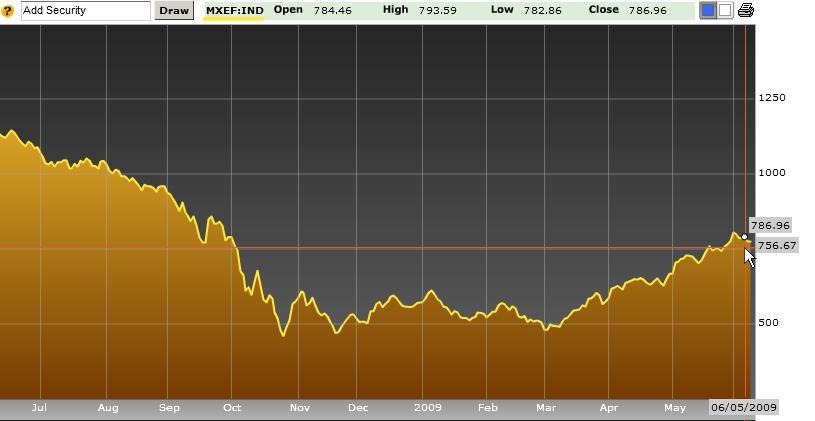

Here are some more statistics. The MSCI index is now at an eight-month high, following a record 61% rise since February. $12 Billion have poured into emerging markets in the last four weeks alone. Consider this against the backdrop that “Earnings at companies in the MSCI emerging-markets gauge

Here are some more statistics. The MSCI index is now at an eight-month high, following a record 61% rise since February. $12 Billion have poured into emerging markets in the last four weeks alone. Consider this against the backdrop that “Earnings at companies in the MSCI emerging-markets gauge